The Herstory of Feminism

Feminist Icon Series

March 29, 2019

Growing up I was always questioning about what I learned in the little Catholic school I attended for so long. I found myself asking my religion teacher, (which never ended well for me) ¨how come Eve was made from the rib of Adam, why not the other way around?¨ and ¨How come God is a man, and not a woman?¨ I always wondered why there wasn’t a female figure I could really look up to besides my mother. Our president: a man. The religious anomaly I was supposed to be praising: a man. Even my principle, who was a woman, always taught the girls in my class what we needed to do to ¨keep our husbands happy.¨ The moment I realized I was a feminist was when I was in 6th or 7th grade, listening to my social studies teachers tell us about Susan B. Anthony. As I daydreamed in class and stared blankly at my textbook, something she had said stood out to me, ¨No man is good enough to govern any woman without her consent.¨ For whatever reason this quote felt like it hit me in the face, and I wondered why that throughout history, in media, in school, that women were at the foot of man. My curiosity lead me to discovering the (her)story of feminism.

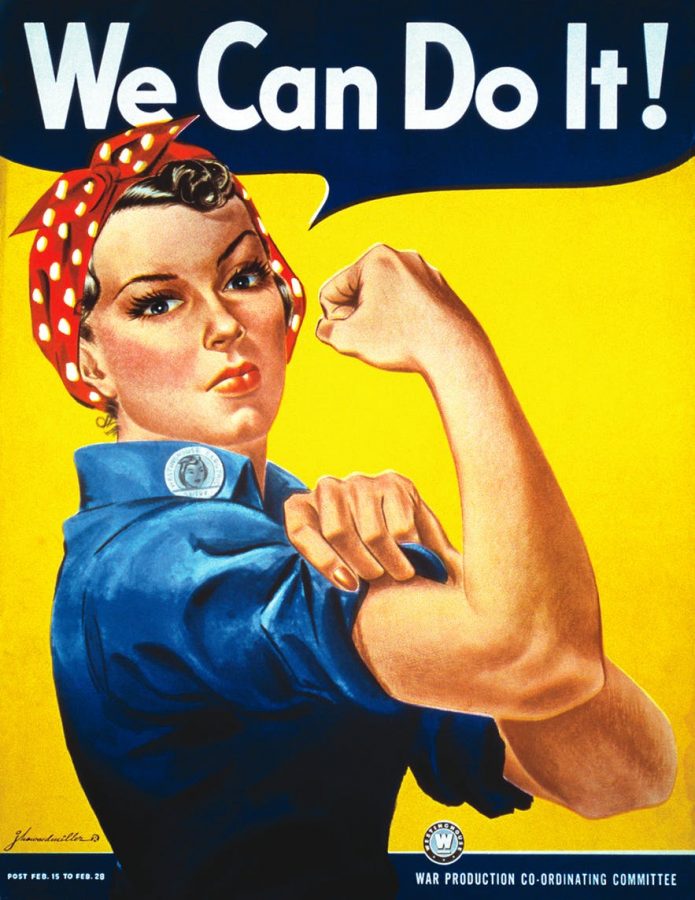

The first acknowledgement of feminism was by Simone de Beauvoir who wrote, (in regards to the french author and feminist Christine de Pizan´s Epistre au Dieu d’Amour (Epistle to the God of Love)) that this was “the first time we see a woman take up her pen in defense of her sex.¨ This was documented to be sometime in the 1500s. Feminist scholars have created three ¨waves¨ of feminism. The first wave targets the strides women took in the 19th and 20th century in the US and UK. During this time women began fighting for their rights. It began with fighting for the right to their own property and equal contract, abolishing the ownership of woman by their husbands, and gaining recognition in leadership positions. In the early 1900s the Women’s Suffrage Movement sprouted, and brave women like Susan B. Anthony and Jane Addams paved the way for future generations, while getting women the right to vote. During World War II, Rosie the Riveter was created to encourage women to work, and she became the face of feminism, and according to History.com, ¨American women entered the workplace in unprecedented numbers during the war, as widespread male enlistment left gaping holes in the industrial labor force.¨ Simply having a woman figure to look up to, real or not, inspired thousands of women.

The Second and Third Wave of feminism blend together. Technically, scholars have labeled ¨The second wave as lasting from 1960-1980. This period of time focused more on attempting to end discrimination towards women, which is why this blends in with wave three, because unfortunately there is still a need to end sexism and discrimination. In the current Third Wave, women struggle mainly in the workforce getting equal pay, trying to stand up for themselves when abused by men, and rise up into bigger political roles. Women have come very far. We are no longer burned at the stake for having more than one brain cell, but we are still faced with struggles of our own, as the women of the 21st century.

The word ¨feminism¨ was created as a way to bring light to the injustice that women were facing and to create a movement that would bring them higher up in the social ladder. This movement began and was created to be a positive force in our world. But to my dismay, this positive word has turned sour due to the negative assumptions about what it really means.

Though the core definition of this word was made to advocate for women’s rights, over time everyone has created a different definition as to what it really means. This word has been pulled in every direction except the one it was meant for. But what does it mean? Does it mean that all women who identify as a feminist want abortions? That they want to ruin men’s lives and take their jobs?

I made the decision to create this series to debunk the negative myths about feminism. More people should feel free to identify themself as such if they feel fit without worrying about the opinions of others who may not even know what the word actually means. In this series I am going to interview different people from both sides, whether they identify as a feminist or are strictly opposed. I’m attempting to come at this from every angle; interviewing professors, such as Professor Mary Kearny, the head of gender studies at Notre Dame, teachers here at Adams, such as Ms Stanton, younger students and older business people. I’m going to write about the #MeToo movement, the term “feminazi,” and gender pay gap. I’m here to figure out why this once positive word has become so negative in the eyes of millions.